I was never sure if I actually believed it — the story about my Yia Yia and the way she decided her fate. Choosing between two men and two countries. I’ve always been intrigued by this tale, and would ask her or my aunt Bess, uncle John, cousin Georgia or any other relatives sitting around our dining room table on Sundays —to please clarify anything they could remember about this great story.

My grandmother Dionecia Safari was born in 1906 Amaliada, Greece, a small village of 200 people. She loved writing and reciting poems about living there - she wrote pieces about orange blossoms, ahhh to louloudia to anthisma, others about parrots, to prasino papagalos efage to koukla mou, (This is actually a poem about a parrot that pecks the eyes out of a doll.) She wrote other prose about bright moons, fengariki mou lampros, and her favorite theme, The Mediterranean. “M’aresee to thalassa,” she’d sigh. “I love the sea.”

My grandmother was also a huge fan of Sappho, the ancient Greek writer whose poetry was often sung while accompanied by a lyre.

Dionicia loved sitting on her balconia, breathing in magnolias and playing her mandolin. “Promenaders linked arm-in-arm, would wave to me in my veranda,” she’d recall. “‘Kali spera Dionicia,’ they’d shout. ‘Kali spera, good eee-veh-ning’ she’d nod back.

Everyday Dionicia passed the chorio fountain and pine trees walking to her eklesia, a 700-year-old church, run by Pateras Ioannis— Father John, the priest who christened her, said prayers at her mother’s burial and splashed Holy Water on her forehead each New Year’s Day.

My grandmother spent a lot of time with women. In the mornings, with women she knew from church, she’d embroider bright pink and orange poppies on pillow cases created for dowries. On many afternoons they’d stuff sugar-coated almonds into tulle, then tie the netting with slippery white ribbons. These small koufete bundles were passed out at wedding and baptismal celebrations where friends danced the hasapiko, and yelled OPA!

At night - snels (snails), manestra (orso), and horta (dandelion greens) simmered in large metal katzarolas (pots) for family dinners.

When Miss Safari reached 18, it was time to date and think about marriage. Unexpectedly she received two marriage proposals in the same week: one from an Amaliada - based scholar, the other from an Argos-born businessman.

“At 18, how well could I have known these men?” she shrugged. “Agapou ke tous thio, I thought I loved them both,” she shrugged again. And there was more —the scholar wanted to marry and live in Greece; the businessman wanted to wed and move to America.

After weeks of uncertainty, Dionecia took two cards and wrote “America” on one and “Greece” on the other. “I put theeeeze cards in my pocket and walk to the eklesia,” she said. “My heart is loud. Kane etsi, etsi, etsi. Boom.Boom. Boom. Inside church I light orange candle and push into sand in front of silver Panayia, Virgin Mary icon. I do stavro, make sign of cross. No one is there.”

Kneeling, she placed the names of both countries face down on a cold marble floor and shuffled the cards in front of the images of Jesus and The Four Apostles painted on a gold altar. “Christai mou, fotise me. Please Lord, tell me what to do,” she whispered. Following a long prayer, she closed her eyes and reached for one card: “America.” Her card said, “America.”

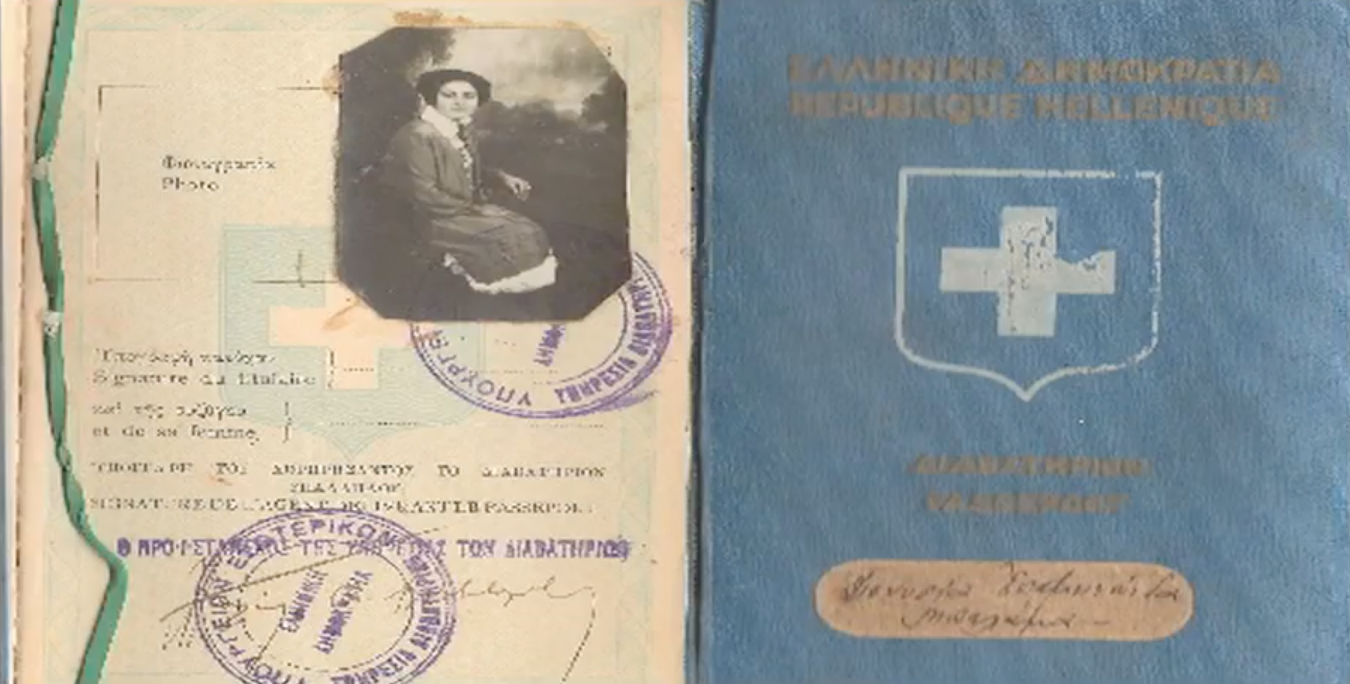

Dionecia Safari married Peter Balamos in Amaliada in 1924, then waved goodbye to Greece with a white hankey from the deck of a westbound ship. After clearing Ellis Island and dozens of train station stops on a journey taking two months, Dionicia Balamos arrived at her new home in Decatur, Illinois, where Peter Balamos opened The American Ice Cream Company. They had three children.

My grandmother never really did learn to speak English or give up cooking snels, manestra or horta. Into her mid-eighties, she continued to write Greek poems about love, the moon, parrots, and dolls; and on many nights sang sad ballads playing her mandolin. S’agapo, s’agapo toso poly agapi mou.

Dionecia passed away in 1997 at the age of 91. Her life-size marble statue of Sappho remained in her dining room long after she died.